***

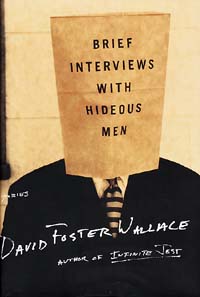

The subject matter of David Foster Wallace’s short story collection Brief Interviews With Hideous Men is nothing new (relationships between straight men and straight women), nor is the dominating perspective (ostensibly white middle-class men). However, the experimental style of Wallace’s prose breathes new life into tired themes and perspectives, taking postmodernist literature to the next stage in its evolution. As a successor to the likes of Robert Coover, Vladimir Nabokov, and John Barth, David Foster Wallace is a natural heir, building upon such techniques as the non-linear linear tale (several stories are annotated tangentially a la Pale Fire), authorial presence and involvement, meta-fiction, and a dry and detached sense of humor. In some cases Wallace literally extends these postmodernist ideas, with long multi-clause sentences and footnotes, keeping the reader from getting too lost in the story and paying attention to his rather exhausting structure of lengthy-but-spare paragraphs and complete sentences. By synthesizing and building upon the style of the canonical postmodernist writers, Wallace continues their legacy and brings postmodernism to contemporary times.

The subject matter of David Foster Wallace’s short story collection Brief Interviews With Hideous Men is nothing new (relationships between straight men and straight women), nor is the dominating perspective (ostensibly white middle-class men). However, the experimental style of Wallace’s prose breathes new life into tired themes and perspectives, taking postmodernist literature to the next stage in its evolution. As a successor to the likes of Robert Coover, Vladimir Nabokov, and John Barth, David Foster Wallace is a natural heir, building upon such techniques as the non-linear linear tale (several stories are annotated tangentially a la Pale Fire), authorial presence and involvement, meta-fiction, and a dry and detached sense of humor. In some cases Wallace literally extends these postmodernist ideas, with long multi-clause sentences and footnotes, keeping the reader from getting too lost in the story and paying attention to his rather exhausting structure of lengthy-but-spare paragraphs and complete sentences. By synthesizing and building upon the style of the canonical postmodernist writers, Wallace continues their legacy and brings postmodernism to contemporary times.The most striking thing about Brief Interviews is the non-linearity of the arrangement of the stories, and the interviews of the title story. None of the interviews printed in the book are arranged in a particularly numerical or chronological order, nor are the numbers consecutive. It’s clear that these interviews are the only ones “selected” for publication, since not all of these interviews are featured. These interviews are scattered throughout the text, divided into four parts, fragmenting them. This was definitely intentional, perhaps only for the superficial reason that the particular style of “Brief Interviews” may get tiresome for the reader or because they went on too long. A variant example of this fragmentation is “Octet,” which in fact has only five sections, and the fifth discusses how the eight sections became four among the other facets of the formulation of the story. “Octet” most obviously contains the classic characteristics of postmodernism, referring to itself, explaining itself, describing how its existence as a story came about, disregarding the conventional notions of character and plot altogether. “Adult World (II)” in fact disregards all formal pretense in its structure, reduced to a mere outline of the plot and character developments. Since it’s such a radical change from the preceding story, one might think that Wallace deliberately changed the tone to avoid and flout convention.

Wallace exhibits the detachment from his characters peculiar to postmodernist writers in a new way, writing of them as an unattached observer, with so much focus on detail that people and plot are all but forgotten. He utilizes this technique in “The Depressed Person” (who is referred to as that throughout the story), “Death Is Not the End,” and “Suicide as a Sort of Present.” The observational (though not usually objective) and often scientific language of these and many of the other stories cultivates the humor that pervades within them. In spite of the tragedies many of these characters endure, the reader can laugh due to the absurdly detailed and matter-of-fact voice of the narrator. Of course, the reader feels sorry for these characters, who often come off as victims of their own circumstances or pawns of plot, but in an abstract and distant way. Even the narrators who are an obvious part of the story (as in “Brief Interviews” and “On His Deathbed, Holding Your Hand”) reveal this sort of detachment from the characters they’re interacting with, due in part to their roles as listeners rather than speakers.

Wallace’s satirical and long-winded prose has evolved obviously from the postmodernist writers of the 60s, and his observational narrative style a more modern adaptation of their detachment from their subjects. He took postmodernist literature to new lengths, showing that even a movement that had become old hat could be revitalized and made anew in the face of a new century. After all, literature, like all art forms, always has room to evolve.

No comments:

Post a Comment